Greetings, friends,

An astute fiction writer once wrote, “Every man has the same dream. All that varies is their mode of transport.”

He wrote this because he knew that, though some great travel writing has been written by women, the desire to cast off the shackles of civilization and head out for parts unknown is primarily a male urge.

Journalist Carl Hoffman, after spending years reporting from some of the most dangerous places in the world, decided to carry this urge to an extreme. His plan was to go around the world, his modes of transport being only the most statistically dangerous buses, boats, trains and planes. He chronicled his experiences in his book, The Lunatic Express.

At first this seems like a journalistic stunt, and Hoffman admits that, like so many other middle-aged dudes hitting the road after an existential meltdown, his own personal life had hit a serious snag.

But he also had a legitimate journalistic goal: to show how the rest of the world gets around.

Here in the western world, we complain about the vile drama of air travel, with its overbearing airport stooges herding us like cattle and frisking our under wear, and the sulking flight attendants that we who fly in steerage have to abide.

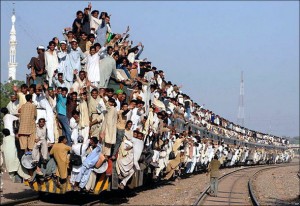

But these are luxurious conditions that the rest of the world would envy. And Hoffman shows himself, and the reader, no mercy in portraying the almost heroic measures the people of the rest of the world must undertake, just to get around.

He writes, “I wanted to jump on and circumnavigate the planet on that unseen artery of mass transit. I wanted to know what it was like on the ferries that killed people daily, the buses that plunged off cliffs, the airplanes that crashed. I wanted to travel around the world as most of the people in the world did, putting their lives at risk every time they took off on overcrowded and poorly maintained conveyances because that was all they could afford or there were no other options.

He rides with manic minibus drivers in Lagos, Nigeria, who pilot rickety vans crammed with as many as 30 people as they negotiate the city’s potholed streets

, driving at breakneck speeds, always wary of the cops they have to pay daily baksheesh to, working sixteen hours a day, chewing a narcotic weed to stay awake, just to earn the meagerest of livings.

He rides jammed ferries in Bangladesh, ramshackle buses with bad brakes through the Andes, takes listing, overloaded passenger boats down the Amazon, and takes a hair-raising mountain passage through Afghanistan over washed-out roads policed by gun-crazy Afghan fighters. True to the spirit of his journey, he flies on the world’s most dangerous airlines.

But the most heartrending tale of the travel woes of the world’s poor is that of the trains in Mumbai, India. Each day, millions of Indians board these relic trains which ride over decaying rails, packed together like canned meat. IndiaDaily reported on May 9, 2012,

In the first three months of the year, 805 commuters have lost their lives and 867 injured in train-related accidents.”

This was no statistical anomaly. So many Indians die from the simple act of getting to work that most of the train stations have morgues to handle the bodies.

Hoffman rides these trains

, of course, but he concedes that he could not have survived this experience, or his entire journey, if not aided constantly by some of the world’s poorest people, and he finds daily reminders of the truth many travelers learn; that the most generous people on earth are the ones who have the least to give.

To stay sane, Hoffman develops, in the face of all this danger, a sort of phlegmatic attitude. He stops fighting the nastiness and the dirt and the delays and the dangers, and as he lets go of his resistance, he slips into a form of misery that he comes to find almost comforting.

In quieter moments, Hoffman meditates on the nature of travel. He has plenty of doubts about his motives for this trip, but in the process of his ruminations, he brings to light one of the most prominent myths about the nature of arduous journeying.

It is widely believed that getting away to parts unknown is a form of self-escape. But that might not be true. At home, we are surrounded by evidence of our identity and our importance. We have a reliable source of feedback telling us who we are and what our purpose is and what our next move should be. We live out our lives nestled in this relatively comfy cocoon

, where our most cherished illusions about ourselves are constantly reinforced.

But try landing in an Asian or African city at midnight, knowing nothing about the currency, the customs, the language or the culture, and you soon realize that one misstep on your part could place you at the mercy of strangers. With no familiar cues to guide you, you are, in the most frightening way, completely on you own. Short of facing a terminal disease, there are few more stark confrontations with your true self than this moment of appalling aloneness.

If you’re simply trying to escape your circumstances, the rigors of travel may not help you

, because they can make you constantly yearn for the comforts of home. If you set off on a journey to find yourself, you may learn things about yourself you wouldn’t really care to know

One thing strikes Hoffman no matter where he goes; the unfailingly upbeat attitudes of the people he meets. When he asks a man how he can remain so genuinely cheerful in the face of his difficult life, the man says,

“But you never know when you will die. So you must be happy all of the time.”

Wise words indeed.

Here’s wishing you happy travels on safe modes of transport, my friends,

Bruce

Sources;

Carl Hoffman, The Lunatic Express, Broadway books. 2010

IndiaDaily, may 9, 2012

The Starboard Bar, from The Dark Side Of Enlightenment, Stanfield Books, 2014