Three-Legged Love.

Greetings, friends,

The world of classical music has certainly known its share of neurotic geniuses, but few have ever reached the level of other-worldly genius and sheer neurotic goofiness as the great Canadian pianist, Glenn Gould.

Recognized at an early age as a musical genius, Gould was gifted with an astonishing memory, allowing him to memorize a musical score after one or two readings. He had a perfect sense of pitch and an audial acuity that allowed him to differentiate between the slightest variations in tone.

But along with these gifts came character traits that were both endearing and frustrating to those he dealt with. He was annoyed by the stuffy formality and conservatism of the classical music world. In one of his debut concerts, he was instructed by an imperious conductor that all musicians in the orchestra must have their sheet music present during the performance. Gould knew the music four ways from Sunday, but to placate the conductor, Gould walked on stage carrying the musical score, dropped it on his chair, sat down on it, and ripped through the concerto as if he had written it himself.

And that chair he set the music on is a story in itself. Known as “The Pygmy Chair” it was given to Gould by his father when he was a boy, and Gould carried it with him around the world. He was so admired by his fellow musicians that he had to have the chair guarded when he went to the restroom during rehearsals, for fear they would snip off a bit of it as a souvenir. He used this chair to the end of his life

, and for decades, long after the upholstery had worn away, it was held together with wire and spit. Gould loved it because it swayed and rocked as he did while playing, and it made such loud creaks and crackles it gave recording engineers fits trying to edit out the noise.

By the age of thirty Gould was not only a world-renowned genius, but one of the best loved performers on earth. His concerts were sold out months in advance. Women sent him letters pledging undying love. But Gould hated the concert scene. A raging hypochondriac who suffered from insomnia

By the age of thirty Gould was not only a world-renowned genius, but one of the best loved performers on earth. His concerts were sold out months in advance. Women sent him letters pledging undying love. But Gould hated the concert scene. A raging hypochondriac who suffered from insomnia

, he took numerous pills, including tranquilizers. His pillheadedness was well known. He once replied to a newspaper article about it. “The press claim that I travel with a suitcase full of medications. This is a gross exaggeration. It is merely a small briefcase.”

All great artists suffer frustrations

, but it may be that Gould’s lifelong search for a suitable piano that could allow him to manifest his colossal gifts was his greatest burden (aside from his wacky personality, of course.)

Part of the problem is that a genius such as Gould hears music in his head that he is constantly trying to bring into the world of sound. But he is always hampered by the physical limitations of the mechanical device he uses to make that sound real. Gould had such delicate touch, such lightening-fast, “butterfly” fingers, and such a sublime technique that he doubted he would ever find a piano that could suit him.

As with all concert pianists, dozens of Steinway Grands were always at his disposal. Gould tried hundreds over the years, but like a man searching for the perfect woman, there was always frustration.

He had already resigned himself to the limitations of the Steinway, a piano built to create the resounding volume required to deliver the Romantic composer’s music to the concert audience. But Gould thought the Romantics were narcissistic and showy. He was a Bach man all his life

, and had only one goal – to interpret as faithfully as he could the great Johann Sebastian’s intentions.

For those of us who haven’t dedicated our lives to music, it may be difficult to understand the intensity of the relationship between the musician and his instrument. A superb account of Gould’s frustrating search is chronicled in Katie Hafner’s book “A Romance on Three Legs.”

She does a brilliant job of elaborating the inherent problems of a concert Grand piano. Built of 12,000 parts, made of wood, wire, felt, cotton and iron, “these massive, seemingly robust, even indestructible instruments could be orchid-like in their fragility, prone to any assortment of ailments”

And the variations among the instruments themselves is immense. Two Steinway Grand’s, built in Astoria by the exact same technicians, one after the other, using the exact same techniques and materials, will be completely different in their personalities.

But Gould relentlessly continued his search. Then one day in June of 1960, in the basement of Eaton’s department store in downtown Toronto, while wandering among the dozens of Steinways in the basement, he pushed back the keyboard cover of a dinged-up ebony grand, played a few notes, and instantly he knew…this was the one.

It was Steinway # CD318, a beat-up old warhorse of a piano. It had been hammered on since 1945 by dozens of concert artists, and had been shoved aside, awaiting shipment back to the Steinway factory for rebuilding.

But CD 318 was in such bad shape that it would require the ministrations of an unusual piano technician to revive it, and such a man was Charles Verne Edquist, known to those in the piano world simply as “Verne”

Edquist’s road to prominence in his field was as rutted and rocky as Gould’s was fortunate. Born into implacable poverty in rural Saskatchewan, he had lost 90% of his vision in early childhood, and at the age of 11, having never been outside his village, he boarded a train that would carry him across Canada to a school for disabled children. Piano tuning was a common trade for the sight impaired

, and Verne took to it immediately, spending decades working his way up to the top.

Tuning a piano is only one aspect of the repertoire of skills required by a competent technician. Verne had the ability to completely disassemble the piano, go over every part of it, and reassemble it. One of the most difficult skills is the “voicing” of a piano, which involves the kneading and sanding of the felt hammers that strike the strings. Verne was as gifted as Gould in his ability to distinguish tone and pitch, and he was also synesthetic, meaning that to him, sounds had a color component that were as real to him as the reds and blues and yellows that sighted people take for granted. But Verne – he saw them in his head.

Of Verne’s reaction to CD 318, Katie Hafner writes,

“…the first few chords he played on 318 got his attention. He was well accustomed to the different qualities of fine instruments, but in 318 the tone and the featherlight, fast-repeating action stood out. This was a piano with a soul.”

Though Verne Edquist and Glenn Gould were different in many ways, when it came to producing the music, they were brothers under the skin. Gould had long since given up performing in concerts and had dedicated himself to recording the works of the Baroque Canon. At each recording session, Verne was nearby listening intently, and when there was even the slightest slippage in CD 318

, Gould would stop playing and nod to Verne, who often had heard the problem already. Verne descended on the old piano with his tools, and when the problem was solved, the recording continued.

This collaboration resulted in some of classical music’s greatest recordings, and no doubt would have continued until one of the men died. But it came to a tragic ending in September of 1971. The beloved CD 318 had been shipped to Cleveland for a rare Gould concert appearance, and on its way back to Toronto, the crate that contained it was violently dropped. To his day, what happened has remained a mystery. No one has come forward to own up to the tragedy.

Gould and Verne tried desperately to restore the piano, but no matter what they and the experts at Steinway attempted, the magic of CD 318 had been lost forever.

Gould refused to give up. He continued to urge on anyone who would attempt to restore the piano’s greatness, but nothing worked. His response to this loss mirrored his reaction to his failed relationship with the painter Cornelia Foss. They had a torrid love affair, and for years after she left him, Gould tried desperately to get her back, to revive the glory of their time together.

It often seems that those who strive hardest for perfection have the greatest difficulty dealing with the fact that nothing lasts. In the world of classical music, Glenn Gould was a towering giant, but when it came to dealing with the vicissitudes of life, the guy was sadly inept.

Glenn died unexpectedly at the age of 50 in 1982, with a long list of musical projects planned. Had he lived, there’s no doubt that he would have further enriched his already great legacy. Though his premature death was a tragic loss

, his many recordings, most notably those of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, are musical gifts that the world will cherish forever.

That’s all for now, friends. So long, and thanks for listening,

B.

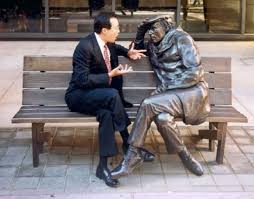

, conversing with Glenn Gould’s statue in downtown Toronto” width=”254″ height=”199″ />

Sources;

Katie Hafner, A Romance On Three Legs

, Bloomsbury, 2008

Kevin Banzana, Wondrous Strange; the Life and Art Of Glenn Gould, Oxford University Press, 1994,

Tim Page, The Glenn Gould Reader, Vintage, 1990