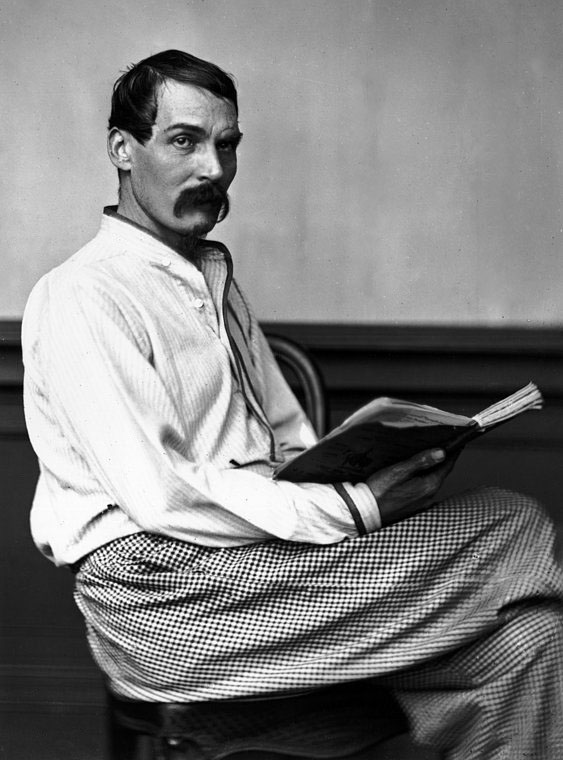

The Most Interesting Man in the World.

Greetings, friends.

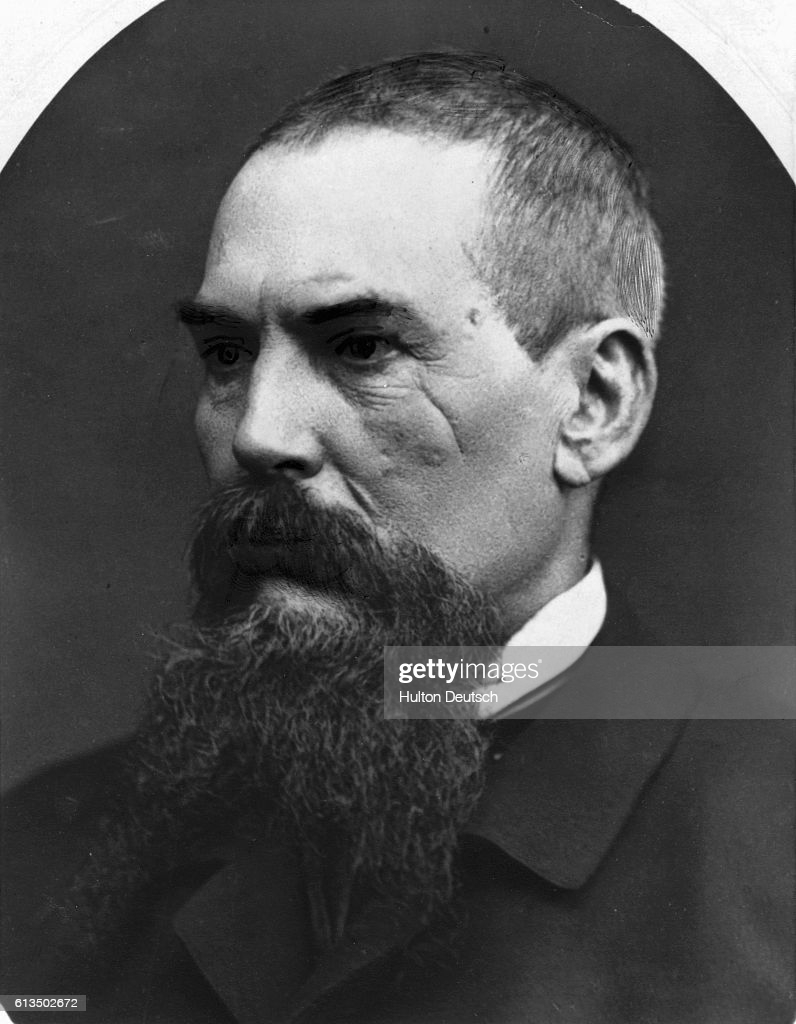

If you look closely at the gent in this picture, you’ll see a scar over his left cheekbone. He had a matching one on the right side, the result of a Somali spear driven through his cheek and coming out the other side, knocking out four teeth and splitting his palate, but staying lodged in his jaws as he ran for his life through the African jungle in the dark of night, pursued by angry Somalis.

For most of us this would be a shattering experience. But after reading of the exploits of this man, you’ll realize it was just a bump in the road.

After all, if you had been the first white man to pose as a Muslim Arab and make the pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina and come back alive, and were the first white man to enter the barbarous city of Harar in east Africa and come back alive, and knew 28 languages and a total of 15 dialects, and had succeeded in being indoctrinated into secret Hindu and Sufi cults, were the best swordsman and horseman and pistol shot in all of Europe, had translated the Thousand and One Arabian Nights and the Kama Sutra, had written 43 books, most of which are still in print,, and for most of your life, in your spare time, were a spy for the British Government, well, a spear through your head would seem, as the British like to say, “a mere spot of bother.”

The chap who owned this extensive curriculum vitae was Sir Richard Francis Burton. One of his many biographers, Edward Rice wrote,

“If a Victorian novelist of the most romantic type had invented Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton, the character might have been dismissed by both the public and critics in that most rational age as too extreme, too unlikely. Burton was the paradigm of the scholar-adventurer, a man who towered above others physically and intellectually, a soldier, scientist, explorer, and writer who for much of his life engaged in that most romantic of pursuits, undercover agent.”

Numerous tomes have been written chronicling the exploits of this man

, so a brief blog post can’t hope to do him justice. All that post can hope to do is show the contrast that exists between a nineteenth century figure of genuinely heroic accomplishment, and the paltry heroes of our own age.Burton was born in 1821 and died in 1890. His childhood was a tale of wanderings with his retired-soldier father and mother of noble birth, parents whom Burton referred to as “professional invalids.” His family lived all over Europe, during which time Burton accumulated languages, learned customs, engaged in bad-boy behavior and, along with his brother Edward, brought scandal to the family and endless frustration to the poor souls engaged to educate them. By the age of nine, Rice states, “Burton was a confirmed juvenile delinquent.”

His father was determined that Burton join the clergy, and returned the family to England so his son could attend Oxford in preparation for a comfy career as a vicar. Never was a man born who was less suited to the clergy than Burton, but few men have been born with his intense interest in religions. Confirmed and dedicated sinner as he would be throughout his life

, he managed to penetrate the deepest secrets of Islam, Hinduism, Sufism, Sikhism, and a list of other cults he refers to in his many books.Of course, Burton’s career at Oxford was brief, his parting caused not only by rebellious behavior but also by disagreements with the Oxford dons over the proper pronunciation of ancient Latin and Greek.

So, what is a parent to do with an upstart son whose passions in life are fighting, studying languages, exploring exotica, and living the life of a sybaritic roué of the first order? Buy him a commission in the military, of course, and wave goodbye to him as he sails off to India.

No place on this earth could have suited a man such as Burton more perfectly than mid-nineteenth century India.

From the moment his ship landed, he was repelled by the squalor and stench, the bizarre customs of the natives and the slovenly behavior of the British. and entranced by the sights and smells and exotic mores, the strange other-worldliness of India. Tropical heat, fever, bad food, silly military customs, all of it served to frustrate and inspire him, and he thrust himself into Indian life with his typical passion, immediately taking up the study of Hindi, Persian, Urdu and various dialects, absorbing the native customs, taking mass quantities of port wine to wade off fever, opium to ease the aches and pains that Asia can heap upon the white man, and enjoying easy sex with native women. After easily passing the regimental exam for Hindi, Burton had immersed himself into Indian life so thoroughly that he became known to his fellow officers as “The White Nigger.” It was this talent for disappearing unnoticed and living among the natives that made him so valuable to his superiors, and which created an unbroachable gulf between him and other Englishmen. To the end of his days, Burton, though idolized by the British public, would never again be considered, a “perfectly proper chap.”

But that life of immersion would lead to his future role as invaluable agent. Rice writes,

“What Burton was heading for, unaware and naively

, was a role in what came to be called, “The Great Game,” a game of secret intelligence that was as deadly as it was sporting and was one phase of the shadowy war between England and Russia over native territories in Central and west Asia.”For six years, between stints of regimental duties, Burton periodically slunk off among the natives, disguised as a variety of native types and castes, gathering information, delivering messages, negotiating with potentates and mass murderers until, despite his iron constitution and iron will

, he broke down physically and mentally.According to Rice, Burton, “seemed to be shriveled with some unknown disease, perhaps a fever, He was confined to quarters in Karachi, isolated, a ‘White Nigger.’ By the beginning of 1849, he decided to go home; seven years behind him, work, sport, women, languages dangerous expeditions into places where no white man had ever ventured before, among people who flayed enemies alive, put out the eyes of brothers, sons and fathers in their dynastic quarrels, kept women in a kind of prison, (and where women were given captives to castrate, slowly), all part of an experience no man had ever had before, and so far as anyone can tell, no one has repeated or is likely to.”

Burton’s friends in India feared he was dying. But on the long voyage home his immense recuperative powers brought him back to life, and by the time he reached England he was somewhat restored. But he felt his years in India had been time wasted.

Edward Rice writes

, “He had achieved prodigious feats, but had gained no rewards. Daring, intelligence, talent, and a cool head in danger had been negated by Burton’s own sensitivity to and scorn of army politics.”To rise in every military and political hierarchy, a certain amount of bootlicking is required. Burton just never got the hang of it.

So, despite his immense service to the Crown in The Great Game, none of his work helped him departmentally. But his experiences would enable him to write numerous books, and most important, Edward Rice says, “he had gained a vision of Islam through personal experience that was to lead him to Mecca.”

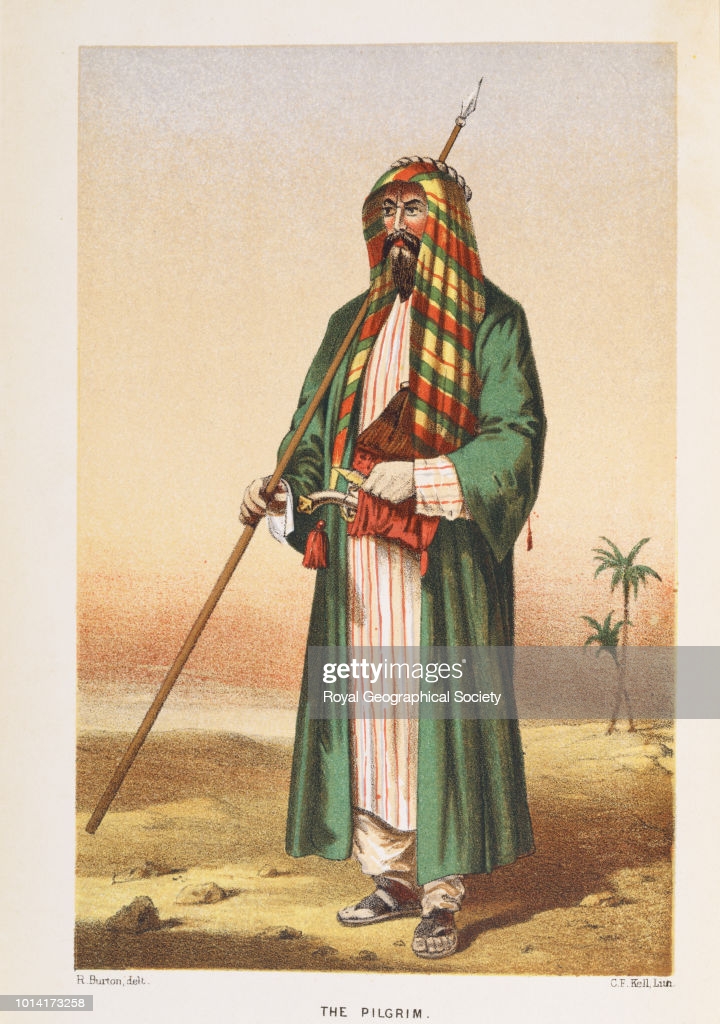

For the next four years Burton lived mostly in Italy. He wrote books, studied, honed his swordsmanship, lapsed often into the black depressions that haunted him his entire life, and chased women, eventually in Bologna meeting his future wife, Isabel Arundel. But marriage was not on his mind. He was honing his Arabic and his knowledge of Islam, and after those years of what he termed “effeminate living,” he approached the Royal Geographic Society with a plan that would have been, for any other man, suicidal. Burton proposed to disguise himself as an Arab dervish and travel with other Moslems on the obligatory pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina known as the Hajj. His purpose, or so he stated to the Royal Society, was to survey, “the huge white blob which in our maps still notes the Eastern and Central regions of Arabia.”

However genuine Burton’s motives to study the inner life of the Muslim and to gain geographic knowledge may have been, it is the humble opinion of this writer that Burton’s primary reason for this adventure was simply to prove to himself that he could come out of it alive.

We must consider for a moment what this entailed. First, he had to speak Arabic like a native. Arabic is a language on par with Mandarin in it’s difficulty. but Burton had mastered it completely. He had steeped himself in the study of Islam so successfully that, when his fellow travelers suspected him of being an imposter, he overwhelmed them with his vast knowledge of their religion, forcing them to drop their suspicions.

So he set off on what remains to this day one of the most epic human adventures, recorded in minute detail in his two-volume account, “Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Medinah & Meccah,” It’s impossible to appreciate what an accomplishment this journey was without reading these two volumes. At peril of his life, Burton made copious notes on tiny slips of paper, wanting to assure the accuracy of his account of the journey.

After accomplishing this tidy little jaunt, what could such a guy do to get his adrenal glands pulsing again? Well, why not go to East Africa and try to enter the ancient city of Harar? According to Rice, “It was a holy and forbidden city, No white man was ever believed to have gone there, though many had tried. The bigoted ruler and barbarous people threatened death to the Infidel who ventured within their walls.” After gaining entrance to Harar, Burton was detained by it’s vicious Amir, but after securing the Amir’s friendship with the British government, Burton escaped and made his way to safety.

But all along, he had another adventure in mind; since already in Africa, why not head into the jungle and search for the source of the Nile river?

This epic journey nearly destroyed Burton’s health, and his unfortunate alliance with traveling companion John Henning Speak would lead to years of vicious public disagreement. When Burton returned to England he was a walking cadaver. Months of vile food, tropical heat, insect bites, protracted bouts of high fever and living with death only inches away had worn him out.

He would later write blithely of the spear-through-his-face episode, and list the hardships of the journey with the usual British stoicism, but not even a man such as Burton could come out unscathed. One strange note; Burton had been examined by doctors before his African trip and was diagnosed with secondary syphilis. But when examined on his return to England, the syphilis was gone. Weeks of intense fever had killed the bug, but not Burton.

Once again, his health still dangerously decrepit, Burton wrote more books, argued publicly and in journals about the accuracy of his arch-enemy John Speke’s account of their Africa journey, and tried desperately to persuade Isabel Arundel’s family to allow him to marry her, but they refused.

So, what does a chap such as Burton do to get healthy again and forget his frustrations? He sails to North America and boards a stagecoach in St. Joe, Missouri, for a bone-jarring ride across America, to see and record in detail the sights, hoping to engage in some idle fighting with Indians and also to see the Mormon settlement in Salt Lake City and interview Brigham Young.

While on this journey, Burton wrote. “The City of the Saints, and Across the Rocky Mountains to California.” This 577 page, detail-packed tome, is considered to this day to be the definitive text describing the conditions in the American West just before the Civil War. One has to wonder, reading Burton’s books, how he could possibly have written in such detail while enduring so many hardships.

After he reached California, Burton hoped to cross Mexico but was unable, due to circumstances beyond his control, to do so. A man bent on exploration hates to leave any stone unturned. Burton writes;

“For this disappointment, I found a philosophical consolation in various experiments touching on the influence of Mescal Brandy upon the human mind and body.” (p. 501)

When Burton returned to England he finally succeeded in marrying Isabel Arundel, and after all his years of service to the Crown, hoped to be appointed consul to Damascus, but as Thomas Wright says in his biography of Burton, “Those mysterious rumours due to his inquiries concerning secret Eastern habits and customs dogged him like some terrible disease.” Burton was appointed consul to Fernando Po, a dismal graveyard for white men in Spanish West Africa.

Burton was bitter about this lowly post, saying, “They want me to die, but I intend to live to spite the devils.” So after saying goodbye to his wife Isabel he left for Africa, and during his tenure wrote four more books on African customs, used his free time for constant explorations of the African interior, picked up a few more languages and further cemented his place as the founder of the science of ethnology.

Burton was eventually posted to Damascus and served there from 1869 to 1871, then sent to Trieste. During these years he travelled ceaselessly when he could escape from his consular duties, piling up more manuscripts and translations, writing more poetry and sending frequent dispatches to the Crown.

Burton and Isabel spent their final years in Trieste, and in 1886 he was knighted by Queen Victoria. He died in 1890, his 69 year-old body finally giving out.

At the time of his death

, Burton’s workroom contained twelve large tables, each piled high with works in progress on archeology, language studies, geology, bizarre customs of little-known tribes, and a collection of erotica gathered over his decades of travel.Soon after his death, his wife Elizabeth, being a strict Victorian Catholic and eager to protect her beloved husband’s reputation, burned nearly all of this material, committing to flames a priceless treasure of information that no other man in history could have compiled

, and making herself, to this day, one of the most excoriated females in British history.As noted earlier, this is but a brief sketch of Burton’s life, but this overview suffices to show how meager are our modern heroes. The human race doesn’t make guys like Burton anymore, and most likely never will. His personal code was best expressed in a stanza from The Kasidah, an Arab poem he translated;

Do what thy manhood bids thee do, from none but self expect applause.

He noblest lives, and noblest dies, who makes and keeps his self-made laws.

Sources:

Fawn M. Brodie, The Devil Drives. A life of Sir Richard Francis Burton, W.W. Norton, 1967

Edward Rice, Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton, Charles Scribners & Sons, 1990

Thomas Wright, A Life of Sir Richard Francis Burton, two volumes, London Everett & Co. 1906

R. F. Burton, City of the Saints, and Across the Rocky Mountains to California, Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York, 1862

Isabel Burton, A Life of Sir Richard F. Burton, Chapman & Hall, 1893

“